One way or another, the global climate deal signed December 2015 in Paris is historic. But in what way, and where does it leave us now?

Perhaps the best one-sentence summary comes from environmental leader Bill McKibben, who said the deal "didn't save the planet, but it may have saved the chance of saving the planet."

It's an odd statement, but it makes sense when you look at what happened. In this article, we'll explore what it means.

There are two seemingly contradictory ways you can view the Paris deal. On the one hand, there are those who are breathing a sigh of relief. After all, an international climate deal was signed, and in some ways it was actually better than expected.

On the other hand, this positivity largely exists because expectations prior to Paris were so low, because of previous failures. For all the fanfare, the fact remains — the deal doesn't save the planet. Many in the world are now left figuring out how they will handle the devastation they are already seeing, or that is locked in by this deal.

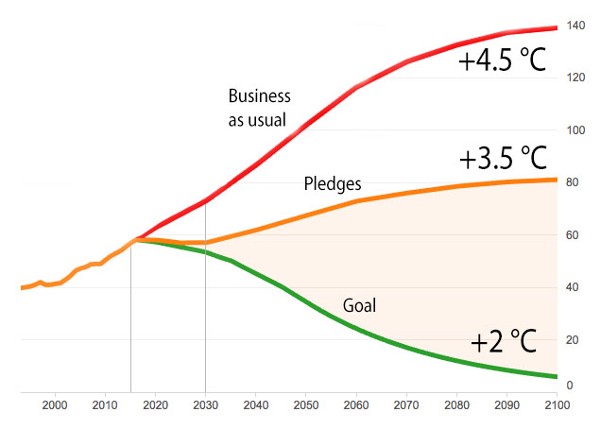

Let's put it another way. The combined pledges submitted by nations could, if implemented, shave degrees off expected global warming. That's a good thing. The down side is the numbers submitted are nowhere near enough to avoid the catastrophic nightmare scenarios predicted for this century.

Given that scientists have explained that the deal still leads to catastrophe, how might we say it "saved the chance to save the planet?"

The answer lies in the idea that the positivity of the Paris moment could represent an inflection point, after which the world's response will rapidly ramp up to match the reality of the crisis.

The 'saving the planet' part comes next

For this to happen two elements are essential. First, we must make sure that what was agreed upon actually happens. The emission-limiting pledges countries made are not compulsory, and therefore there is a significant risk that countries will not live up to them.

Second, we must press — hard — for an sharp increase in ambition.

To understand why, consider the consensus that a global temperature rise above 2 degrees would be a very dangerous path for humanity. Scientists tell us that crossing this boundary would almost certainly lead to irreversible tipping points, sealing our fate.

The Paris deal acknowledges this problem, and even points out that we should aim muchlower than 2 degrees. However, the combined pledges made by nations still fall well short of the target — less than half of what's required to hit that 2 degrees.

Our current trajectory leaves us with coastal areas including huge world cities inundated by rising sea levels. The loss of farmland will trigger large-scale drought and mass migrations across the world, leading to the multitude of refugee crises, ethnic tensions and global conflict that inevitably follow.

We have enough of those problems now, we certainly shouldn't be asking for a huge uptick. Especially when we consider that emissions reduction now are far cheaper and easier than costly mitigation efforts in the near future.

What the Paris deal does do is signal the end of the fossil fuel era — but not quickly enough. The scariest part is that this trajectory runs us leaps and bounds over a 'tipping point' from which these planetary changes become irreversible.

That tipping point could be as little as 17 years away, and by the time we see the worst of these effects, any chance of turning back will be distant in the rear-view mirror.

To beat that, the climate fight must continue, and intensify sharply. There is little time left to avoid such tipping points.

The moral chasm

Who stands to suffer the most from climate change? The impacts are not spread evenly. In fact, the scale of the injustice at play here is staggering.

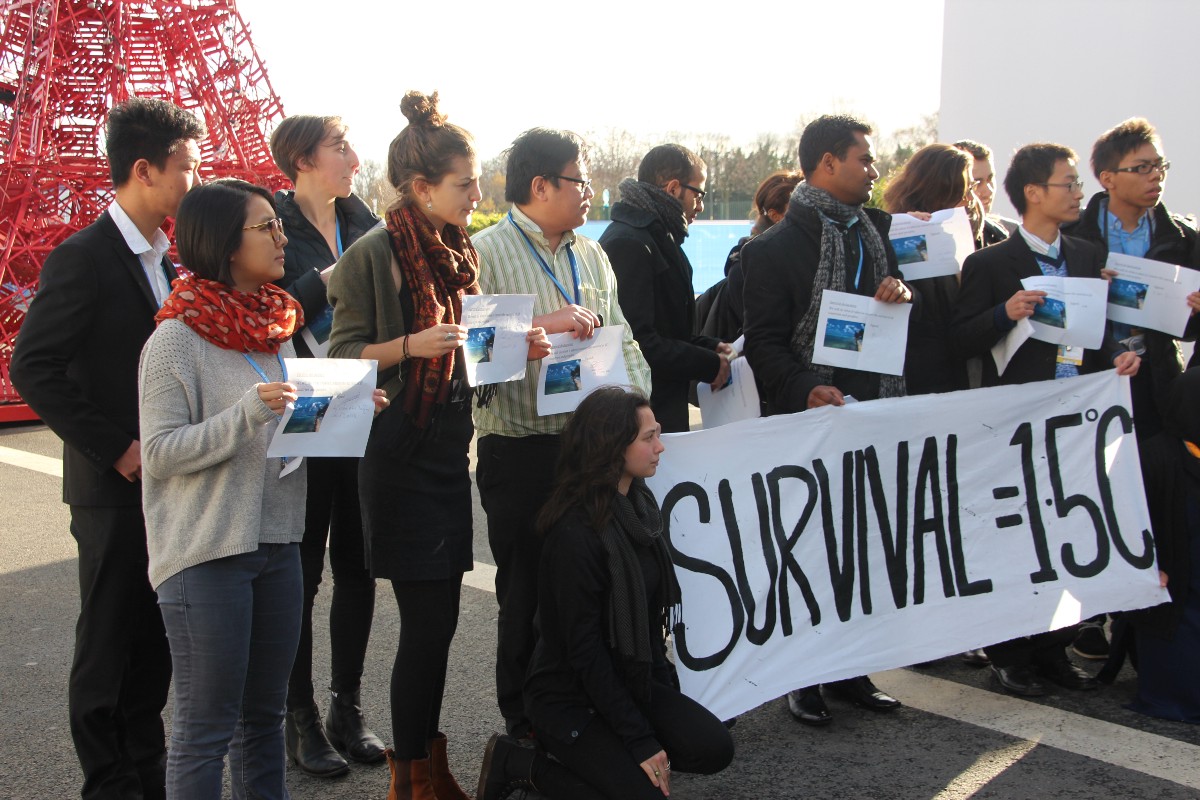

People living in poor nations, having done the least to cause or benefit from climate change are being hit first, and hardest, and that trend will continue. For hundreds of millions around the globe these threats are existential — that is, people stand to lose their homes and their lives.

Meanwhile, those in rich countries who pollute most aggressively have the wealth necessary to buy their way out. Having known about this moral crisis for more than 30 years, rich nations have chosen to keep polluting rather than rapidly transitioning to renewable energy sources, sealing the fate of poor nations in the process.

This vast moral chasm is the reason you'll see calls for 'climate justice' at campaign rallies, and even in the text of the Paris deal.

The final deal does briefly acknowledge 'climate justice' — a first for a deal of its kind. However the deal uses non-binding language, and there is no mechanism at play which will enforce the actuation of that justice.

Poor nations were successful in getting a target of 1.5 degrees mentioned in the deal as an aspirational target below the 2 degrees. Achieving this would be good news for both rich and poor nations — the further we keep from that 2 degree mark, the more likely we are to avoid those irreversible tipping points.

However, reaching either of these targets is unlikely without a major, fast, sustained shift in global energy production. As we have seen, the pledges made by nations so far don't even get us close.

Hope comes in a world-war effort

Nations agreed in the deal to ratchet up their pledges every 5 years. This means the framework is in place by which we could conceivably hit the goal of less than 2 degrees, if we consistently come back with much more aggressive targets.

The scale and rate of industrial change required to achieve that are orders of magnitude beyond current attempts. Entrepreneurial inventor Saul Griffith compares this to the USA retooling for World War 2, during which industrial production tripled each year. As Bret Victor points out, that's more than twice as fast as Moore's law.

We know that this rapid industrial retooling is necessary to save millions of lives. But we are not doing it. Why?

This is one of the central ironies of climate change. The human brain is wired to respond forcefully to threats from dangerous people, like Hitler and the Third Reich. Wider-scale systemic threats like climate change don't register in the same way — even when they are just as urgent and much more dangerous.

The fossil fuel industry has played off this psychology to keep its profit margin high at the expense of people's lives. Combating this cynical exploitation, and provoking real action requires large-scale education and political pressure.

That's where campaign organizations come in.

Driving things forward

Campaign organizations like 350.org mobilize people around the world and amplify their voices. They are consistently impressive in crafting smart, innovative and creative messages through high-impact demonstrations and community-building.

Organizations like this have been crucial in supporting global climate marches and demonstrations, the fossil fuel divestment movement, and the ultimate rejection of the Keystone XL pipeline.

Many such campaign organizations exist as part of a thriving ecosystem, each playing a particular role.

The organization ClimateTruth calls out the 'disinformation' which does so much to paralyze political action to curb climate change. The Indigenous Environmental Network amps up indigenous people's capacity to protect themselves from existential climate threats.

These organizations have been picking up serious momentum recently as the climate crisis intensifies. However they need to be a lot more successful if we are to keep those tipping points at bay.

To understand the impact of organizations like these, consider this. The scale of the changes we need to make are huge. They take effort, they cost money, and more often than not we need politicians to initiate or implement them.

So politicians have the power to make change, but they can only do so with popular support. It's enormously important that we educate people about the crisis and ask them to channel popular support to politicians and other leaders who make real change a priority.

That's what these campaign organizations do — educate and empower people to speak out, and put pressure on world leaders to act on it.

For these campaign organizations to be successful in achieving these goals, they need support from everyone. In a very real sense, if you understand the incredible urgency of this crisis, this means you.

It's hard to overstate how important it is that this crisis be part of your local conversations, with family, friends and colleagues. The more people talk about climate change, the more pressure it applies for a political response.

A good place to start is to sign up for 350.org alerts, and prepare to be consistently inspired. You can also drop me a line if you want to know more about how artists and technologists are getting involved, or to discuss and learn more.

Fighting back

We mentioned a war analogy earlier on, and that's a good way to view this issue. The climate crisis is like an enemy at the gate.

To succeed in this fight humankind must operationalize, productionize and push. We can't rely on the political class or campaign organizations to carry this alone. Pressure has to be felt from everybody.

There's an immense positive in all this, if we choose to see it. Beating back global climate change may be like fighting a global war, however it's different in one crucial way. This time we are all on the same side.