I was trying to tell a friend the other day how Git and Github are related. Where does Git end and Github start? What do they each even do for you?

I realised that it's actually one of those fundamental things that is worth stepping through and getting a clear understanding. If you've been using the terms interchangeably, the distinction makes a good backdrop to learn more, and getting clarity will enable you to steer past a whole bunch of confusion later on.

What is Git?

Well, Git is not Github. Git is a piece of software that you install locally on your computer which handles 'version control' for you.

So to learn about Git, you have to learn about version control.

What is Version Control?

Let's say you have some new project, and you are planning to store all the files for that project in some new directory. You know that as time goes on, the files in this project will change - a lot. Things could get messy, and who knows when you might need to revert back to a previous working version of what you had?

So, you install Git on your computer. Then, you have Git create the new project directory for you. You also tell Git that you would like to keep a history of the changes you make within that directory.

Then, you add some files to kick off your project. The files you just added represent the first incremental step on the journey of your project. So you tell Git to take a snapshot.

Then you make a small change - your next incremental step. So you take another snapshot.

And that's about it for version control - make a small change, take a snapshot, make another small change, take a snapshot. You can then use Git to step back and forth whenever necessary through each snapshot (snapshot aka version) of your project directory. Hence, version control.

And Git is just one of the many version control systems out there, that you can download and install on your machine. Hence, Git.

Collaborating with Git

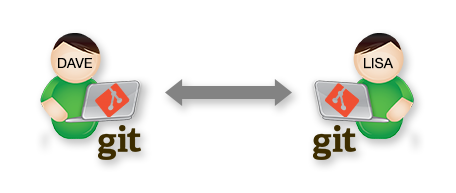

That's great for you as an individual. But what if you are working on a team, and you want to share your project directory? And you want to make changes on your machine, send those changes to your collaborators, and also have changes they make appear in your machine's project directory?

Git is a so called distributed version control system. All that means is that Git has commands that allow you to push and pull your changes to other people's machines:

Neither copy of the project directory is any better or 'greater' than any other - you are both collaborating on identical copies. This is a good thing, and Git gives you the power to work on your own copy as-is until you are ready to pull in your collaborator's changes, and push back your own changes.

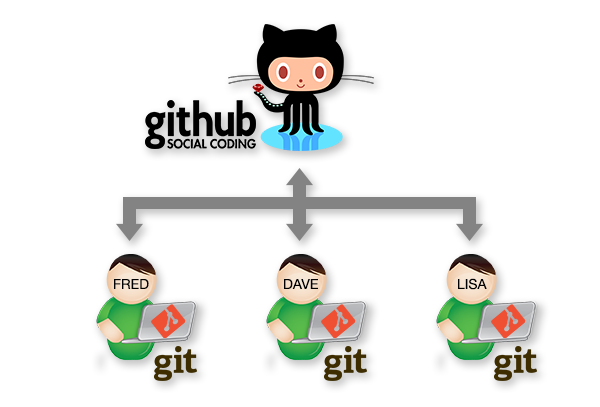

But unless you are working right next to each other every day, you can't be sure exactly when your collaborator will have their machine on and plugged into a network. Wouldn't it be great if there were a third identical copy you could both push and pull from?

Collaborating with Git and GitHub

Well, that's what Github is! At it's core, it's just a place to store your identical working directories - aka repositories, or repo's for short. That's the service that Github provides - it's literally a hub for Git repositories.

Github gives you a bunch more features, like a nice website to allow you to compare changes and administrate user accounts. But it's raison d'être is to host your repos, and to make it easier for you to push and pull from your collaborators.

*Not* just a hosting service!!

One common mistake people make is thinking that because Github repo's are public by default, that it is essentially just somewhere to host and share your code when it's done. This is one thing you can do, but if that's all you are doing, you are missing the real power of Git.

Where Git really excels is as a collaboration tool. A place for you to Do It With Others. If you are doing all your coding on your local machine and then just uploading it in one snapshot (aka commit) at the end, you are missing out on a huge amount of value.

Git allows you to snapshot/commit incrementally, after each little change you do. I regularly have 10 commits per day, and I or anyone can cycle back and forth through those snapshots any time we like. People can see how my thinking evolved - the early commits are experimental and the project has barely begun to address it's aims, and the later commits are more mature and the project is getting close.

Commit early, commit often

But the larger benefits of commit early/commit often are that other people can see and comment on what you are doing. You are being collaborative and open, and the feedback, suggestions or help you get along the way might just alter the entire course of the project for the greater good. It might well save you a whole bunch of time, help you discover some previously unconsidered potential, or even identify an awesome collaborator who will help you drive your project forward.

Opening out your half-baked thoughts sounds scary to some, but we all go through those stages - and those are the times when feedback and engagement is most critical. If you don't want the world to see your project, you can always create a private repo and pull in collaborators by invitation only.

Alternatives to Github

Since Git and Github aren't really linked - Github is just another place to store identical repos - you could use any Git hosting service. One alternative is Bitbucket. This service gives you free private repos (unlike Github), in case you aren't ready to share your work with the world.

However Github is the most widely used Git hosting service, and has a broad community of users sharing code and interacting.

How to Learn Git

So in any case, the real challenge when you are starting out isn't learning Github, which is just an interchangeable service which allows you to host the thing of real value - your Git repository. Your attention is better spent learning Git.

The best way to learn Git in my opinion is this free online book: git-scm.com/book. It walks you through step by step and assumes no particular knowledge. There is an online, PDF and mobi version available, and it uses Github for hosting when you get to that stage.

There are a lot of topics to cover but for most users interacting on a fairly small scale, the first two chapters should suffice. You can pick up the harder stuff as and when necessary.

Another good place to go if you want to try out a few commands without going through the hassle of installing Git, is Try Git. Expect some commercial ad tie-ins, and it won't answer your questions like the book does. But it does let you give things a try and learn by doing.

Good luck!